Hide

hide

Hide

Transcript

of

Branscombe Church, Devon

Devon & Cornwall Notes and Queries vol. VII, (1912-1913), Exeter: James G. Commin. 1913, illus., plan, pp. 1-19.

by

Edith K. Prideaux

Saint Winifred’s is among the oldest and most architecturally significant parish churches in Devon. The 12th century square central tower is one of only four completely Norman towers in Devon. Characteristic Saxon chiselling on stones hidden in the turret staircase suggest the probability of an earlier, 10th century, Church on the site. The building has a traditional west-east alignment. It is built on a levelled area that cannot be seen from the coast. The choice of location may have been for protection of the original Saxon church from Viking raiders. Alternatively, the church may have been placed on an earlier pre-Christian holy site. Occupying such a pagan site would have allowed the Church to both challenge paganism and benefit from any positive religious feelings associated with the site. The article, from a copy of a rare and much sought-after journal can be downloaded from the Internet Archive. Google has sponsored the digitisation of books from several libraries. These books, on which copyright has expired, are available for free educational and research use, both as individual books and as full collections to aid researchers.

Interesting accounts of the parish church of S. Winifred, Branscombe, Devon, have been written already, and it would have seemed that there was hardly any object in bringing it again before the public had it not been that the opportunity has occurred this year (1911) of securing photographs and measurements of the church while under repair, which may serve to elucidate some doubtful points in its architectural life-history. And it is here attempted to put these into a concise and chronological form for the consideration of those who may be interested in one of the oldest churches in Devonshire.

Each stage of English church-building history and custom is well illustrated in its walls and furnishings, from the earliest stone-building period down to the time of 'horse-box' pews; and we will proceed through them step by step, as these unwritten records lead us, utilising the side-lights of written history only where they distinctly throw our architectural facts into clearer relief. In the booklet by the present Vicar - the Rev. A. Steele King - on 'Branscombe; its Church and Parish, (1) a large amount of valuable matter respecting the church, as well as the whole parish, is included; and, as a record for residents and a hand-book for visitors, nothing could be more complete than this well-illustrated little volume. I am, personally, much indebted to Mr. Steele King for his ready permission to take photographs and his assistance in obtaining the measurements and information that I sought; and I should like also gratefully to acknowledge here the help I received from the foreman-of-the-works in my measurements, and the obliging manner in which his workmen put up with, and forwarded, my intrusive work among them.

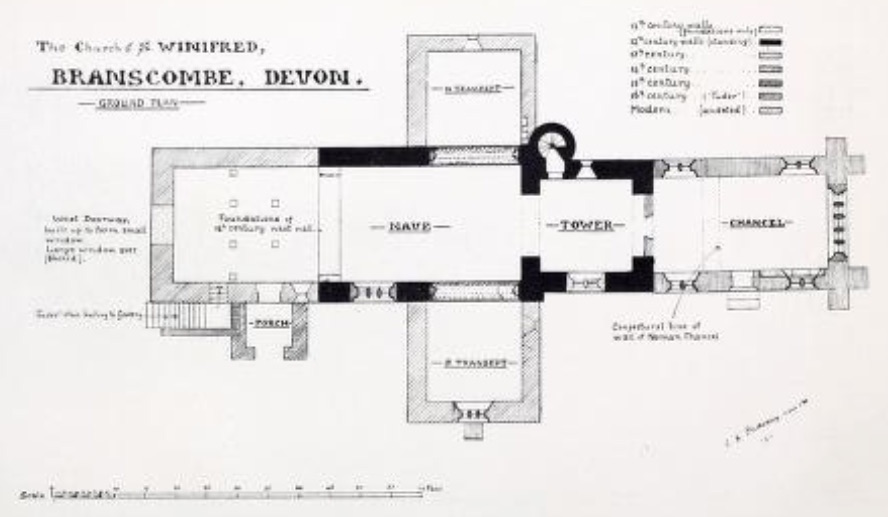

Plan

The plan given here is of the church as it now exists; but on it is indicated by means of varied hatchings the chronology of its walls; and there is also shown, in blank outline, walls no longer existing, of which either the foundations have been excavated or other evidence obtained for their former existence ; while single dotted lines show merely the conjectural position of walls.

First Period: Twelfth Century.

By this plan it is therefore clear that the surviving architectural record begins with the tower and a short nave, the latter having been subsequently altered, but the former being as we now see it, rather late Norman work (twelfth century), with the exception of the top stage of the circular stair turret, and some of the lights in the belfry-stage, and the south window in the ground stage. But, in the lower part of its walls, on the inside is some masonry pronounced to be of much earlier date, and distinctly pre-Conquest in character (2). Therefore, we may reasonably conclude that the original church standing on this site was of pre-Conquest date, and very possibly included a tower of which this masonry is a portion ; but as to the form and size of the rest of the church there is now so little clue that it cannot appear on our plan even in the conjectural dotted line. Probably it was a small, rectangular, aisle-less building with perhaps a low central tower ; and the desire for a larger and more important church, when the great wave of Norman church-building was passing over the country, produced in this remote and secluded western Combe-of-many-branches the Anglo-Norman church which is the earliest to be represented on our plan.

Possibly another testimony to the existence of an earlier tower may be found in the fact that the late-Norman stair-turret is not bonded into the tower masonry at its lowest courses, these being, perhaps, the base-courses of the early tower. Photo No. 4 shows a part of the junction of the masonry where the turret joins the north wall of the tower on the eastern side, from about three feet above the ground for about eight feet further in height (3).

It is, however, declared by some authorities that there is good reason to believe that the greater part of the present tower was built upon the site of the Saxon chancel; but on this point the evidence is scarcely conclusive.

Also, the existence of the present thirteenth-century transepts - or, more correctly speaking, transeptal chapels - in their very unusual position, west of the tower, is suggestive of there having been chapels on the same site - though probably much smaller - in an earlier church. These may have belonged to the Saxon church, in which they would probably have opened out north and south of its tower, as a ground-plan of this quasi-cruciform character is not infrequently found in late-Saxon churches ; and in such cases, when a twelfth-century church was built on the same site, it was usual for these earlier transeptal chapels to be retained in plan, though generally enlarged in size if not totally rebuilt. In fact if, as seems possible, the twelfth-century church of Branscombe had transeptal chapels in the same position as the present ones, that is a fairly strong argument in favour of the existence of some form of transeptal chapels on the same site in the Saxon church ; for the normal position of transeptal chapels in a freshly-planned twelfth-century cruciform church would have been north and south of the central tower, and it would have been due to some special cause - such as a rebuilding on a previously occupied site - that transeptal chapels would have been placed west of the tower as they are in Branscombe.

However, it is by no means proved that the twelfth-century church here had transeptal chapels at all, and there is another, entirely different, interpretation of this peculiarity of position open to consideration, for which there seems also to be strong evidence. Allowing that the twelfth-century builders raised their tower on an earlier sub-structure (whether Saxon tower or chancel is immaterial), it is evident that it was built as it now stands, with no north and south openings other than windows. Therefore, when a transept was desired as an addition, the position and size of the turret precluded the subsequent cutting through on the north side of an archway of a sufficient size for an opening into a transept, or transeptal chapel. This fact would quite account for the builders of the thirteenth century (to which period the present transeptal chapels entirely belong) having broken through the nave walls west of the tower in order to form their transeptal additions.

Therefore, seeing that conjecture must play so large a part in the imaginary reconstruction of the Saxon church, and in the absence of further evidence of the existence of early transeptal chapels, I have preferred to adopt this latter very simple theory, and have accordingly on my plan laid out the twelfth-century church as seems to me to be best supported by existing evidence, although at the same time admitting that with regard to the non-existence of early transeptal chapels I may be mistaken.

As here shown this twelfth-century church followed a plan very common for small churches in the period of its erection, which was probably the second half of the twelfth century, after the Canons of Exeter Cathedral had, in 1148, become the Rectors of the parish(4). This plan consisted of an aisle-less nave (often set out on one and a half, or two squares) ; a square tower, practically forming the choir, of very nearly the same width as the nave, sometimes even wider ; and a short sanctuary beyond, either, as at Hadleigh and Copford, Essex; Iffley, Oxon (originally); and Birkin and Lastingham, Yorks, - in the form of a semi-circular apse; or, more often, of a rectangular form after the pattern of the east-ends of the Saxon wooden churches, - as Greenstead, Essex; and many of the pre-Conquest stone churches of the country, - as Corhampton, Hants; Dunham Magna, Norfolk; and Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts.

It is only, lately, during the present work of restoration (1911) that the position of the original west wall of the twelfth-century nave has been clearly disclosed ; the quoins at the north-west angle are still in situ, and the westward extension wall on that side was never even bonded in with the original north wall on its internal face, though externally bonding-stones have been liberally introduced. Parts also of the foundations of the original west wall are in position and run as shown in blank outline on the plan. It is noteworthy that, taking the interior measurements of the old twelfth-century nave from this original west-wall to the tower west-wall, we find they are calculated on one square and a half of 19 feet 4 inches; then comes the tower-square of 15 feet 3 inches (internal space) ; and it would be a very safe conclusion to estimate the interior of the short chancel - whether apsidal or rectangular - as extending eastward a half-square of about the same width as the tower, viz., say 7 feet 6 inches. These measurements, actual and conjectural, give us a church of very ordinary Anglo-Norman proportions, as we frequently find that the ground-plans of such churches are laid out on a system of squares and half-squares.

Above ground, we still have of the twelfth-century church the whole tower, and its turret (excepting the top stage), and the walls of the nave from the transepts westward for about 18 feet.

The tower, inclusive of the parapet, rises about 55 feet from the ground in three stages of diminishing height separated by strings of about 9 inches in depth, and topped with a parapet of over 3 feet deep ; within this parapet — Dr. Cox tells us (5) it measures 19 feet 7 inches square, while its interior measurement at the base is 15 feet 3 inches. The turret rises by means of its last stage - the octagonal addition of a later period - to about 9 feet higher ; its base diameter is 8 feet. Photographs 5 and 6 give two aspects of it, and No. 3 shows a portion of the old corbel-table on its western face. Of the three belfry windows on both this and the eastern face, the centre one only is of the date of the tower, each stage having been originally pierced with only one, narrow, round-headed light, as still seen in the two upper stages in the south view of the whole church (No. i). In the north face of the ground-stage, the old, narrow, round-headed window still exists, and is being opened out ; in its blocked state it is seen in photo No. 4, and [in No. 8 we have its internal aspect when first cleared of the blocking masonry and plaster (6). Facing it the present window in the ground stage on the south side (photo No. 7) is a modern insertion, neither original nor beautiful in design, but doubtless very useful for the present-day requirements of the tower- space within. Below this modern window can be seen externally two built-up, doorway-like openings (photos Nos. 7 and 9) with pointed-arched heads ; these, from their form, are clearly not of the same date as the tower itself, and their purpose is doubtful ; but most probably they were pierced for use at the time that the nave was being lengthened and the transepts built in the thirteenth century (see page 12), when the tower with the little Norman chancel beyond was all of the church that was available for the services, and no doorways into them previously existed. The ground outside them - which has become much raised - is being levelled, which may throw more light upon their date and purpose.

In the central stage of the tower there are two good-sized doorways facing east and west, now built up ; these are not visible from the outside, being within the gables of the roofs, but the western one could be seen within from the nave when the plaster was removed from above the western tower-arch. Their purpose seems to have been to give access to the interior of the roofs in both directions, above the flat ceiling with which doubtless the twelfth-century nave and chancel were originally covered ; and as the central tower-chamber from which they open was then apparently a dwelling room for either the priest or a 'watcher' of the church, there may very probably have been other apartments over the church, constructed in this roof space, - a not very uncommon feature in early mediaeval churches. The height of the external walls to the eaves is about 20 feet in the nave and 17 feet in the chancel and the roof line about 15 feet higher; this would leave space within for rooms of quite convenient loftiness.

The pointed tower-arches (see No. 32) now existing were re-cut to their present shape possibly during the next building period, or later, having doubtless been, originally, semi-circular, and lower by several feet. Their plain, unchamfered edges, however, are a survival of their earlier character.

The masonry of the tower has, naturally, undergone a good deal of patching and strengthening at various times.

Besides the tower and its details, there survives of the old twelfth-century work the eastern 18 feet of the nave walls with some of their original corbel-tables, much worn and patched, and renewed in parts. The corbel shown in No. 13 occurs on the south side near the junction of the nave-roof with the small tower-buttress (7) that occupies that angle ; this corbel may belong to the next building period, - the thirteenth century, when the transept was being added at this point, but that shown in No. 14 is from the north side, and, from various evidences, seems to belong to the original work.

Second Period: Thirteenth Century.

The next building period of the present church was in the early part of the thirteenth century, and to it obviously belong the north transept and the extension of the nave westward, while the south transept, though doubtless planned at the same time and measuring the same every way as the north, may not have been finished till later. Indeed, if its beautiful early-geometrical window is a part of its original building (No. 11), it cannot have been finished till well on in the second half of the thirteenth century; but the little buttress added to the south wall below this window suggests that it was an insertion subsequent to the building of the wall itself, which showed signs of being dangerously weakened by the enlargement of the window opening. This wall is now found to be the most ruinous part of the whole church. The north transept retains externally its early character throughout, and is still lit only by its single lancet in the north wall (No. 12).(8) This lancet measures 10 feet 3 inches in height by 2 feet wide externally, including jambs, - glass 18 inches only; the internal splay brings the width to about 4 feet ; the sill is 7 feet 6 inches from the rough ground externally, and 9 feet 6 inches from the paved floor within (as it was recently). There is no rebate in the jambs, which shows that it always was a glazed window, and not merely closed with a shutter as were many early lancets.

There are no corbel-tables to the transepts, and the continuation of this feature in the contemporary westward extension of the nave was doubtless made for uniformity with the earlier portion of the nave walls ; the spacing of the corbels is noticeably wider in the later portion. That this western extension is contemporary with the north transept is shown by the class of window by which it was originally litj one on the south side being shown in its built-up condition in No. 10, now, happily, being again opened. It is so similar in character to that in the north transept (though its proportions are not identical) as to be an absolutely sure guide to the date of the wall in which it occurs. There are none now visible in the north wall of the nave.

The western extension measures 27 feet in length. Its terminal wall was evidently re-built or altered about a century later, but the blocking of the west door and window is of a much later date still, probably that of the eastward extension of the gallery (see pp. 16-17).

Turning now again to the south transept- still a piece of thirteenth-century work, though probably the latest portion of this enlargement of the church- we find there are clear indications in the interior masonry (9) of its eastern wall having held formerly one, or possibly two, narrow windows (No. 16). They cannot be mistaken for piscina or aumbry niches, as, for one thing, they are far too high from the floor level for

such, (10), and also the jamb of that on the left hand - the most northerly - can be seen rising to a considerable height, as of a window.

In one of these gaps was found embedded a piece of fine carving (No. 17) of evidently later date than the transept ; but its appearance here - where it was merely built in as blocking material - suggests that this wall was tampered with and its windows built up at a late period, probably post-Reformation, when little care or reverence was shown for such a work of art as the one of which this fragment must have formed a part, and its existence as an altar reredos or part of a shrine or monument was ample reason for its destruction or degradation. If these two gaps - or either of them - are the remains of lancet windows, as seems possible, the inference would be that this transept was absolutely contemporary with the northern one, and that - as before suggested - its south window was a later insertion.

Assuming that no early transeptal chapels existed in the twelfth-century church, the unusual position of these thirteenth-century transepts is accounted for - as before suggested (see p. 4) - by the fact that the stair turret on the north side of the tower did not leave sufficient space for an opening into a transept of a dignified and desirable width; the archway, so limited by it, would have been narrow and inconvenient, and the north transept itself much narrowed internally by the width of the turret. Had the twelfth-century builders planned a transept as an integral part of their own, independent plan, they would have put their stairway in the thickness of one of the angle-walls, where the transept opened out, and have reinforced its stability with internal piers, as at N-Newbald Church, Yorks; (see accompanying plan); but the thirteenth-century builders, finding this course impossible, cut through the nave-walls for the openings into their transepts, and then lengthened the nave to give the church better proportions as well as more accommodation. Transepts were, in one way, a more advantageous addition than aisles, as affording greater eastern wall-space for the multiplication of altars, and in some cases each arm of the transept was even furnished with two altars, each dedicated to a different saint, though this was not the case at Branscombe.

Another fact that may have influenced the thirteenth-century builders in the matter of their erection of transeptal chapels, is that at Branscombe the ground slopes away so steeply to the south of the nave that it may have been they were turned aside from the more usual method of enlarging a church - i.e., by adding aisles to the nave - when they realized how unsuitable and troublesome the site on the south side was for such an extension; and they therefore resorted to the plan of constructing transeptal additions only. But it must be allowed that it is a point much in favour of the theory of pre-existing transeptal chapels (p. 3) that this course was pursued rather than the more normal one of adding nave-aisles, or at least a nave-aisle on the north where no difficulties of site were presented.

The transeptal arches were carried on slender clustered shafts engaged to the wall, of the usual Early English type, with plain, moulded capitals, circular abacus, and ' water-holding ' mouldings on the bases (No. 18), parts of which still remain unaltered, though - as also shown in Nos. 19 and 21 - the original capitals have been mauled and maimed in a subsequent reconstruction of these arches. As they now stand, the arches are of two orders with no mouldings, but merely plain broadly-chamfered edges. It may have been that the original arches did not prove strong enough for the work assigned to them, and that therefore the inner order was rebuilt later, of a much greater massiveness than the Early English capitals were calculated to accommodate. The mouldings of the awkwardly super-imposed capitals (not all alike, cf. Nos. 18, 19 and 21) indicate that this re-construction was of the next building period - the fourteenth century. There are no traces of any carvings of the thirteenth century, and probably the funds were not abundant enough to allow of anything beyond the plainest construction.

Of the porch (No. 15), it is difficult to speak with certainty, partly on account of the absence of any characteristic mouldings, and partly because of its unusual form of archhead. As regards the latter, even supposing that its present form is as it was originally, it must be remembered that these exceptional segmental forms of arches are not confined to any special period and afford little or no clue to the date of the building in which they occur. The porch-masonry, which is of the same kind as that of the thirteenth-century wall to which it is attached, makes it appear quite probable that - although obviously an afterthought - it was added only a little later than the date of the building of the wall itself ; and the near kinship of its plain chamfers in lieu of mouldings to those of the priest's doorway in the early fourteenth-century chancel (No. 24), also seems to point to its having been erected just after the completion of the nave and transepts, when - as remarked above - funds were at low ebb. Plain double chamfers, such as these two doorways show, were in frequent use for plain parish-church work at this period - i.e., c. 1280 to 1315. It has been supposed by some that the porch was a part of the same work as the adjoining outer stairway to the gallery, more than two centuries later in date; but against this theory is the fairly conclusive fact that the masonry of the two appears absolutely different in character (see No. 27), and is not bonded together at their junction.

A reasonable inference regarding the thirteenth-century enlargement of the church is that suggested by Dr. Cox in his interesting article on Branscombe Church already referred to, (11) viz., that it was due to the interest or patronage of Walter Bronescombe (or Branscombe), a native of this parish, who was Bishop of Exeter from 1258 to 1280, and kept up his connection with his early home throughout his life. He was a man of great activity and power of mind, and made his influence felt throughout his whole diocese. The most beautiful monument in Exeter Cathedral is that erected in the thirteenth century to his memory, where his effigy lies on a raised tomb in dignified simplicity, though, unfortunately, beneath an ornate and almost vulgar canopy of pretentious design, added, with more zeal than discretion, in the fifteenth century. It is worth while to draw attention here to this monument of the great Branscombe Bishop (No. 20), both for its own special beauty, and also because this same Bishop was undoubtedly responsible for the whole planning, and the earliest work of the easternmost portion of Exeter Cathedral, (12) and Branscombe may well feel proud of the link thus established between her own parish church and one of the greatest architectural achievements of the day.

Third Period: Fourteenth Century.

While these thirteenth-century alterations were being carried out in the church the services must have been held in the very confined space of the tower and twelfth-century chancel ; and the necessity for the continued use of these parts accounts for the fact that the enlargement of the chancel was not set in hand until early in the fourteenth century. It was doubtless during the period of this use of the tower and chancel that the pointed-arched entrances through the south wall of the tower were pierced (Nos. 7 and 9).

An enlarged, and, generally, rebuilt chancel is more often found than not in the early churches of this country, and Branscombe was not behind-hand in following this very reasonable fashion. But probably by the time the new western addition to the nave, and the transepts were built, some pause had to be made, until a fresh reserve of funds could be accumulated. The pause, however, was not for long, and in fact, the double piscina, cruet niche, and aumbry lately uncovered in the east wall of the north transept are early fourteenth-century work, which looks as if the altar set therein could not have been dedicated till this period, unless these should be successors to an earlier piscina, etc., afterwards built up, which is most unlikely. In the illustration of these details (No. 21) the cruet niche does not appear, as it was not uncovered at the time of my visit ; but, as a rule, neither these nor double piscinae are found in thirteenth-century work.

Of the chancel, the present walls, the lateral windows, priest's doorway, and the beautiful sedilia and piscina are all of the early fourteenth-century building, the east window alone being a later insertion. Even the low transverse wall, in which the quaint seventeenth-century screen was afterwards fixed, is said to be of the fourteenth century, which shows that in its original arrangement the chancel was separated from the rest of the church by a substantial screen.

The triple sedilia and single piscina worked in one design in the south wall (No. 22) were hidden behind plaster until this present work of restoration was set in hand. Their form and proportions are still very beautiful, the slight ogee touch given to the arch-heads being particularly graceful, and also definitely indicative of the date of the work. Whatever richness of decoration originally adorned them on the wall-surface we cannot now determine, as all was evidently ruthlessly cut back to an even face for the application of the deathly shroud of plaster. Very likely dainty, carved canopies, or a rectangular, enclosing label surmounted the arches; the present depth from front to back being 1 foot ½ inches, certainly the whole thing may have projected somewhat beyond the face of the wall, as was often the case.

The four north and south windows are all the original ones, except for the renewal of mullions and tracery in those on the north. That shown in No. 7 is the westernmost on the south, and is a good typical example of the small ‘early-geometrical ' window of the first quarter of the fourteenth century.

Internally, below both this window and its opposite fellow, are recesses occupying one half (the western) of the width of the windows above them. In the last-quoted illustration (No. 7) can be plainly seen the external masonry with which this southern one has been blocked up,(13) and this, with other details, makes it a certainty that they were openings through the wall, in fact, a pair of ‘low-side-windows’ of such common occurrence in mediaeval chancels, and so little understood. That these were a part of the original fourteenth-century building of the chancel is proved by the arrangement of the internal string (No. 23), which is carried continuously down the sides and beneath the sills of the niches, instead of being abruptly interrupted and cut through as it probably would have been had the openings been pierced at a later date. This same string originally ran unbroken round the chancel just below the level of the window-sills, but at the east end it was cut away for the insertion of the later window, and the wall is left bare in its place. This is the only internal string extant in the church, and externally it is entirely devoid of any excepting those dividing the stages of the tower and its turret.

The low priest's doorway (No. 24), set in the south wall between the two windows, is of very plain and severe style, with but little in the way of mouldings bestowed upon it.

As before mentioned (page 10), the transept arches seem to have been altered about this same time, or, probably, just after the chancel was finished ready for use. The reason for this alteration must evidently have been some structural weakness, as the awkward adaptation of the arch to the earlier supports shows that a mere desire for the latest style in arches did not influence the builders, and indeed this and their absolute plainness suggests that money for working mouldings, or for anything extra, was not forthcoming.

It seems quite probable that it was also during the period of the re-building of the chancel that the tower-arches were raised and partially re-built, and it may have been that it was this alteration in the east and west walls of the tower that caused - or revealed - a threatening of instability in the transept -arches, and necessitated their being strengthened.

Another expensive item at this point was the roof of the nave, which belongs to this period. This is now ceiled internally with a lofty wagon-shaped plaster and wood ceiling with carved bosses (No. 25) which must have been a century later in date than the roof proper, as the arms of Bishop Nevill (1458-1464) appear on one of these. It seems probable that the west-front and its doorway and window were also re-modelled at this time.

Fourth Period: Fifteenth Century.

The Church was now virtually complete; but the fifteenth century did not pass without leaving its mark upon it, mainly, as usual, in the matter of windows. Perhaps the earliest of these ‘Perpendicular ' or, more correctly, ‘Rectilinear ' - windows is that inserted in the south side of the nave just west of the transept (No. 28). It is of three lights, and transomed, but the tracery is uncusped and produces a bald and meagre effect, not at all on a par with the richness of the east-end window. As its tracery has evidently been much patched and repaired in a decidedly clumsy fashion it is, however, quite probable that in its original state it was cusped.

Fortunately the large five-light east window is a very fine specimen of its kind. It belongs to a date between 1458 and 1464, as is shown by the saltire on the northern termination of its hood-mould, that being the arms of Geo. Nevill, Bishop of Exeter for that period; the other terminal bears the arms of the See. Its fine proportions and characteristic tracery are seen in No. 26. It measures 11 feet across and is about 17 feet in height; the sill is 8 feet from the ground line, i.e., the same height as that of all ' the chancel windows, which is a rather unusually high level for windows on so small a scale as those of the north and south walls. It may be observed in this last illustration, and in No. 2, that the buttress flanking the east window on its southern side rises to a greater height than that on the northern side by about one foot ; probably owing to the fall of the ground towards the south it was found desirable to bring extra counter-thrust to bear upon the wall at this point, and doubtless it is for the same reason that the south wall of the chancel is 6 inches thicker than that on the north, throughout its length.

The other piece of work of this period is the octagonal stage added to the stair-turret of the tower, well shown in illustrations Nos. 5 and 6.

Fifth Period: Sixteenth Century and Later.

The outside stairway and the doorway to which it leads opening into the gallery within (No. 27) are of late sixteenth-century work, having, obviously, been erected at the same time as the finely carved wooden gallery that occupies the western end of the interior of the nave. Dr. Cox tells us that this 4 is the earliest example of which we are aware in any English Church of an outer stairway to a post-Reformation gallery (14). The only other item to notice in the structure of the church is an arched recess in the interior of the nave south wall, just below - though not central with — the inserted ‘Rectilinear ‘ window. It is not very deep, and its height from sill to head is not sufficient for it to have been a doorway; there are no mouldings round it, but on the chamfer of the jambs are the remains of decorative paintings, imitative of shafts, foliage-carved capitals, and mouldings above. Probably this niche was for the accommodation of some specially honoured tomb or memorial, but of its date it is not possible to form any opinion.

Fittings of Various Periods.

Although not, strictly speaking, a part of its architectural history, any account of this church would be incomplete if its interior fittings were not duly noticed. Some of these probably will not be replaced exactly as shown in our illustrations, but those of real importance and character will be reinstated.

The earliest of these furnishings was, doubtless, a rood-screen and loft, no longer extant, but apparently placed in front of the western tower-arch, as a doorway still exists which opened in this direction from the turret stair-way. This would probably have been of fifteenth-century date.

Then in the late sixteenth century was erected the western gallery (Nos. 25 and 29), which originally projected from the west wall for only about 1 1 feet; the back portion was added and the front moved forward at some later period when presumably more accommodation was needed. The carved oak front and supporting pillars of this gallery are well worth close inspection. The whole will now be put back into its original position.

Next in antiquity are the spiral oak altar-rails, and the woodwork of the chancel screen across the eastern tower-arch (Nos. 30 and 31). The former stood originally four-square, about 3 or 4 feet westward from the east wall of the chancel, where they are now to be replaced ; before the present restoration they had been moved up close to the eastern wall, as shown in No. 30. They are work of the Restoration period, c. 1665, and are good specimens of this type of work. Rails set square round the Communion Table had come into fashion much earlier than this, those in Woodbury Church, Devon (now cut and placed continuously across the church from north to south) having been placed there in that position in 1640.(15)

The screen is rougher work, but interesting as belonging to this same period, when the erection of screens was no longer common. In fact this late screen probably owes its existence to the survival of the base-wall of the early fourteenth-century chancel-screen (see page 13) and must not be confounded with the rood-screen occupying a far more westerly position, and erected for a different purpose.

How the church was pewed at this time cannot be determined, but pieces of late Jacobean oak-panelling having been found incorporated with the later deal wall-panelling and pewing, suggests that it had good wooden seatings of some kind - very likely benches with panelled ends.

The oak 'three-decke' pulpit (shown in Nos. 25 and 32) is of a rather earlier date than the deal 'horse-box ' pewing; but it was removed to the south wall of the nave (as shown here) at the same time as the erection of these ugly pews, in 1810. It will now be removed again and placed at the north-eastern angle of the junction of the north transept with the nave. The pewing was extremely rotten before its removal for the present work to be set in hand. The western tower-arch was flanked on its western face, until lately, with the Commandments, Creed, and Lord's Prayer, painted on wooden tablets; and above the arch, as a central decoration, was painted a large Eye from which long rays of light issued, draped on either side with stage curtains looped back with cords and tassels.

Monuments.

It is, perhaps, hardly within the scope of this paper to record the many interesting and curious monuments within and without the church, especially as they are already well described in the Rev. A. Steele King's booklet to which I have referred above. But of those of uncommon interest I insert photographs, as they have not hitherto been well illustrated.

Nos. 33 and 34 are of the monument to the memory of Joan Wadham, occupying the dark north-west corner of the north transept. She was the mother of Sir Nicholas Wadham, the founder of Wadham College, Oxford, and the inscription (restored) runs as follows: -

Here lieth intomb'd the bcdy of a virtuous and antient Gentlewoman descended of the antient House of the Plantagenets sometime of Cornwall namely JOAN one of the daughters and heirs unto John Tregarthin in the county of Cornwall Esq. She was first married unto John Kelleway Esq. who had by her much issue. After his death she was married to John Wadham of Meryfield in the county of Somerset Esq. and by him had several children. She lived a virtuous and godly life and died in an honourable age + September in the year of Christ 1583.'

The first husband is that on the left, with Joan and their twelve children behind him ; and on the right she appears again behind John Wadham in armour, and five of their children behind her ; but it is generally stated that, in all, she had twenty children. Of the arms above, the central shield is that of Mistress Joan herself, and the others are those of her husbands with their quarterings.

No. 35 originally stood against the south wall of the south transept, and was moved up into the sanctuary - as seen in the photograph- in the early part of the nineteenth century. It is to the memory of a member of the Bartlett family, belonging to the locality, who died in 1606, and it shows all the characteristic and unattractive detail of that period.

The slab with its illiterate inscription, shown in No. 36, is only given here as affording an explanation of a peculiarity in the present internal appearance of the south tower-window. The sill of this window is carried down internally to a considerable depth, and one half of it (the eastern) is blocked from its lower edge to the level of the glass by a projecting mass of masonry of which this slab is the face. Evidently in accordance probably with the wish of John Bampfield himself or his survivors, who presumably owned a family pew close to this spot, a kind of vault for his burial was constructed in this awkward position, and as it only filled half of the recess of the window sill, the other half was still left recessed in a most lop-sided fashion.

No. 37 is a memorial slab to one, John Hedmunt, or Hedraunt, on the floor of thesouth transept; it is of Purbeck marble, and said to belong to the fifteenth century. Both the cross it bears and the inscription - "Orate, pro anima, Johis Hedmunt" - are very slightly incised, and the lettering is extremely rough and irregular.

Another raised slab of stone has been uncovered in the floor of the nave of the church, bearing a cross carved in good relief; it is believed to be that of a priest, and of pre- Reformation date.

Many other memorial tablets of more or less interest, but devoid of any very distinctive characteristics, have places in the church.

Edith K. Prideaux.

P.S. - Since this paper went to press some mural paintings have come to light beneath the plaster of the interior of the north wall of the nave. Those already uncovered are opposite the south porch and are figure subjects arranged apparently within round-arched panels, but so far they have not been able to be identified. I have not seen them yet myself, but as they will be carefully preserved I may hope to do so next summer, and if they are capable of being photographed, I may be able to have them reproduced, if desired, for a future number of D. & C. N. & Q.

Footnotes

(1) Sold in aid of the funds for the present sorely-needed restoration of the church, price 1/-

(2) See an article on Branscombe Church in The Reliquary for January, 1909, by Dr. Ch. Cox.

(3) It has been considered by some that this turret is of much later date than the whole tower to which it is attached, and this absence of bonding in the lower courses is taken as evidence in support of this theory ; it is also stated, by those who hold it, that there is only occasional bonding between tower-wall and turret throughout their entire height (see the Transactions of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural Society, 1877, vol. iv., 2nd series, p. 224). I cannot vouch for the accuracy of this last statement, and undoubtedly the turret courses appear for the most part to range with those of the tower, and the strings are unquestionably continuous and uniform longitudinally. Allowance must also be made for repairs to the masonry at divers times, when irregularities in the courses may have been introduced.

(4) See pp. 20 and 21 of Mr. Steele King's booklet mentioned above.

(5) ln the article in The Reliquary already referred to.

(6) The square-headed recess seen below it is the remains of an aumbry of later date inserted in the wall.

(7) This is in reality no buttress at all, but the quoin of the original twelfth-century nave-wall which was wider than the tower (see plan) ; but at the junction of the nave-roof with the tower, this projecting bit of walling was coped, as a buttress would be. (See photos Nos. 1 and 13).

(8) The disfiguring stove-pipe decorating it in the illustration is already removed.

(9) On the exterior no marked indications were visible, but the masonry was much obscured by the remnants of the stems of ivy recently removed when I saw it, and it was not possible to speak positively concerning it; the only photograph including this wall (No. 9) gives merely a sidelong view of it.

(10) I have not the exact measurement, but it would be somewhere about 5 or 6 feet to their sills.

(11) See p. 2, supra.

12) See 'How Exeter Cathedral was Built,' by Prof. W. R. Lethaby, Architectural Review, vol. XIII., March and May, 1903.

(13) The blocking masonry is equally visible on the north side.

(14) See article already referred to. The ugly rectangular window above the porch is a later piercing, probably made when the gallery was extended eastward, and the west-front doorway and window were blocked. It will now be built up, and the gallery put back into its original position.

(15) See Some Examples of Renaissance Church Wood Work in Devon, by E. K. Prideaux ; Devon & Cornwall Notes & Queries, vol. VI.

E. K. Prideaux.