Hide

HIGH SPEN -A HUNDRED YEARS

hide

Hide

Part 3

by Alex Johnson

CRICKET

Many people will be unaware, or may have forgotten that High Spen once had a Cricket Team. The aground was actually at Low Spen and was a lovely spot on a Summer's day. It was named Hugar Road Sports Club and was begun by the Nixon family of, Wilf, Tom, Jack and George. Playing with them was Tot Jackson, well-known as a long-serving bus driver. Frank Buglass, Isaac Walton and all-rounder Milton Gardner also played, I can't remember the team winning any trophies (I may be wrong!!) but I am sure the players enjoyed the games, which is the important factor.

QUOITS

Among the favourite sports of the miners of High Spen till the advent of war in 1939, there was no pastime more enjoyed than playing quoits. Quoits is a very old game. It was actually prohibited in the reign of King Edward the third, and in 1545 Roger Ascham, the famous scholar wrote, "Quoiting is too vile for scholars" for students were neglecting their studies to play quoits.

It gradually regained popularity in the North for it was an inexpensive pastime and it helped to occupy the time for the masses after the chaos of the Great War.

Every local village had their pitches. High Spen had at least four pitches - one beside the Co-op Stores, one on the Recreational Ground (the Rec.) near the Field Club, one beside Road-end Club (The Excelsior) and the other in the Park. Of the village pitches, two were grass and one was a clay-end. A pitch was 15 yards long. The two games were entirely different.

When the hush of evening fell upon the village during the Summer months, youths and men of all ages were to be found gathered round their favourite quoit pitch for a game of quoits or watching their favourite player. The ring of the metal discs could be heard through the still air from afar, the longer the game continued the greater the excitements all the fatigues and cares of the day forgotten under the spell of the game and as the shadows deepened, pieces of white paper were placed on the "hob" to indicate the goal, even by candle light they often played to finish the game - such was the enthusiasm for the sport in the North of England, especially in High Spen. On grass the thrower could make his quoit roll around an obstacle, he could encircle the hob before settling on it. This kind of player preferred a dry pitch, to prevent his quoit sticking in the ground. The clay-end player played a different type of game. The clay-end pitch had at each end a box. The earth here had been dug out and replaced by heavy clay, which was kept moist by liberal applications of water and was usually kept covered with a wet sack to prevent the clay drying out and splitting. The boxes were four foot square and eleven yards apart. The area between the boxes were sometimes rutted by hundreds of footmarks so that it was often timbered to make it easier for the players to walk and throw from. Matches were usually between two players and the spectating miners used these occasions to have a bet on their favourite. Each player had two heavy iron quoits weighing between five and seven pounds each and shaped like a deep saucer with the flat centre cut out. The players threw alternately at the "hob" in the box at the other end. The "hob" was a long iron rod of about one inch diameter driven into the ground till only four inches protruded. When all four quoits had been thrown a point was given to the quoit nearer to the "hob" than the opponents. A quoit circling the "hob" was called a "ringer" and was worth two points. A quoit resting on the hob was called a "jobber" and was a real obstacle to the next thrower. The winner at one end threw first to the next end. The game proceeded till one player scored twenty one and so won the game. In the clay-end quoits were thrown to stand on edge in the soft clay, forming an obstacle. Every village had its champions and High Spen was no exception. Two of the best players were aptly named, they were George Best and Bob Best. Hunter Curry could also throw an excellent quoit.

Quoits were too heavy for children so they resorted to using horse shoes. These were available in quantity at the local pit, from the pit ponies. They were ideal for the younger children who then graduated to using shoes from the farm draught horses before going on to use the quoits.

With the coming of the Second World War in 1939, quoiting gradually died out in High Spen and I doubt if a set of quoits exist today in the village.

FOOTBALL

|

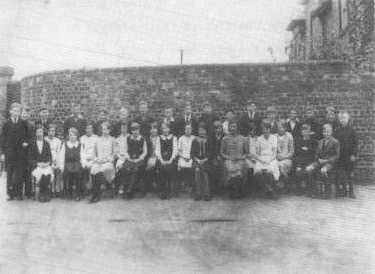

| The unbeatable school team of 1931 Mr N. Smith, Mr Colling, Mr Davidson, Mr Emmerson, Mr Waters S. Lowes, W. Lowden, E. Rennison W. Ebdon, J. Scott, G. Stephenson, J. Gosling, A. Henderson, T. Farrage, Best, J.Wallace |

Football was not a game in High Spen, it was a religion. From being a tiny toddler a boy was expected to be a great footballer. It was said, many years ago, that any club wanting a footballer could shout down a mine-shaft and one would come up. In High Spen where boys were teethed on football laces, a club scout just had to watch the School Team and he had enough stars to content himself. Every season the School Team won cups but probably the finest team High Spen ever produced was in Season 1931-1932. This team won every cup for which they were entered, including the County Cup, a prize indeed.

High Spen had many teams in its history. There was Spen Lilywhites, they player on Barlow Fell, near Pawston Birks Farm. Spen Blues played on the field above the Institute, The Spen Reds above Towneley Terrace as did the Towneley Team but the pride of them all was the Spen Black and Whites, a team feared throughout the North and a team which produced many professionals including the Milburns of Leeds United and Egglestone of Sheffield. Spen Juniors also sent off many players to League Clubs, including Slasher Grant to Everton and Bob Stokoe to Newcastle. The village School Team was respected by all opponents especially in the seasons 1930-31 and 193l-32. Many of these boys played professional football but strangely enough, probably the finest of them all, Cappy Henderson, left school and never bothered to play again.

The village also produced an excellent Ladies Team which included Ethel Armstrong, Alice Watson and the McDermott and Lee Girls among its stars.

EDUCATION

In 1867 a Methodist Chapel was opened at the western end of Glossop Street. It was here that the children of High Spen first received their education. The Marquis of Bute, who owned the Spen colliery donated £10 per year to help pay for a teacher. He also allowed Mr. Andrew Eltringham, the colliery clerk, being good at figures to do some teaching at the school.

|

| The Schools, 1910 |

|

| A class of High Spen School 1931/32 |

In 1875, Mr. Thomas Armstrong became Head Teacher and remained so till after the new board school was opened in 1894. His salary then was £30 per term and he had six pupil-teachers under him! Four of these were his own children who, having left school as pupils, returned as trainee-teachers.

The wages of the teachers in the early days came from a levy of 1d a week per child. Sometimes the pit was working short-time, so the miners didn't pay their levy, much to the exasperation of the Headmaster.

Inspectors visited the school annually and tested the children on their knowledge. Payments to the teachers were on results, so some teachers flogged the children in their efforts to instil learning into them. Many teachers must have been on the bread-line!!

In 1870 the first Education Act was passed. School Boards were elected and in 1876, the power to enforce compulsory attendance became general and the leaving age was raised from 13 to 14.

It was not till 1894 however that High Spen got its own Board School, for by this time the Chapel building was unable to cope with all the pupils registered in it.

The school still stands today and is used as a Junior School.

For many years the Board School was controlled by Mr. Coulson, a stern Headmaster. He died in 1931 and a plaque was erected in his memory, in St. Patrick's Church by the British Legion. He was succeeded by Mr. Davidson who will be remembered by many of those still living in the area. On his staff were Mr. Robert Emmerson (a war-time hero) Mr. Newark Smith, Mr. Waters, Mr. Colling and Miss (Ganny) Hind.

CLUBS

|

| The Road End Club in 1912 |

It has always amazed me how a village like High Spen could support three clubs and two pubs, but it did, and they all thrived. So much so, that they gave away many pints of free beer to members at holiday times. They were also very generous to their pensioner members.

The Excelsior (better known as the Road-End Club) is the oldest. It began in 1885 but moved to its present site in 1913. Jack Armstrong was steward at that time.

The Field Club began in Ramsey Street in 1903 in a wooden hut, but did so well, that in 1910 it moved to its present site on the Recreation Field. Years ago the beer in the cellar was kept cool by a spring which gurgled its way through the cellar.

In 1912 the smaller Central Club (Headsey's) was started. The steward for many, many years was Jack Heads and the local men still call it Headsey's after him.

When the War finished in 1918 and the soldiers returned home, they wished to retain the comradeship formed during those dreadful years so they opened the Ex-Servicemen's Club in a shop in Front Street. Mr. Jack Bousfield was the steward. Unfortunately, due to the competition from the bigger clubs, it only survived a few years.

MINES

From discoveries made in ancient workings it is believed that coal has been extensively worked in the locality of High Spen for over five hundred years. Barlow Fell, Chopwell and Kyo areas were riddled with shallow drift mines and bell shafts. Miners from High Spen whilst working at the Clinty Drift Mine, actually broke through into old working, found a passage held up by pillars of coal and in it they discovered a clay pipe, about two feet long and a pair of leather sandals, as used by the monks of the Middle Ages. These were taken to "bank" and sent to a museum.

Records tell us that in 1728, John Wild of Low Spen and his horse fell down a pit.

Following the sinking of the Bute Mine at High Spen which was opened by the Marquis of Bute and Mr. Simpson of Bradley Hall, a waggonway was built to connect to the existing one from Barlow Fell to Derwenthaugh. This line eventually ran from Chopwell Colliery through Chopwell Woods across Barlow Fell to the top of Thornley Bank, where the waggons were released, to run by gravity to Derwent haugh pulling up the empty waggons by the endless rope principle.

Later drift mines were opened around the village connected to the main pit, there were The Clinty, The Towneley, The Tilley and The Ruler.

The miners worked in dreadful conditions and deaths were frequent, injuries being everyday occurrences. Two of my Uncles, Bob Donnelley and Bob Johnson died through pit accidents, and my father was brought home one day with spinal injuries due to a rope snapping and whipping him.

When someone was killed in the pit, the buzzer sounded and work stopped at the pit. The whole village was silent, wives stood in groups, waiting anxiously to hear which family was to suffer. Being such a close-knit community the whole village grieved at the death.

In my Father's day Mr. Redpath was the Area Manager, living in splendour in Beda Lodge. Mr. Strong was the Colliery Manager and Mr. Rooney the Under-Manager. Not once did I hear my father say a wrong word about any of them.

Working in such dark, damp and cramped positions with very little light caused much arthritis, rheumatism and eye-trouble.

These poor people often in great pain, knew that should the boss hear of it, he would have to give them notice, which would mean even more poverty and worse still - eviction! They persevered and went to work sorely crippled. One miner, Joe Armstrong could not bend his neck at times and his entree into the mine could be traced by the sounds as he bumped his head on every roof truss. There was also Geordie Charlton of Collingdon Road, who could hardly walk in-bye so gladly accepted a lift in a tub pushed by a workmate, often Stephen Waters. Geordie was so grateful that he always marked the first full tub for Stephen. Mr. Strong himself was well aware of these happenings for he himself was crippled with arthritis but tried hard not to show it. The Clinty was a drift mine, a good two miles over the fields, above Prudhoe. It was close to Prudhoe Hall, the local asylum, and the inmates used to wander up to the mine. One day carrying a huge piece of coal, an uncle of mine met one of the Hall residents near the drift mouth. Feeling sorry for him uncle offered him the coal to take back for his fire. Looking at the huge piece of coal the man said, "You must think I'm crackers!" and walked away! Another time he expressed sympathy with an old man, who looked at him with a smile and told him not to be sorry, this was the most comfortable home he had ever had. Evidently, after tramping the country for years he had pretended to be insane, and now lived a comfortable life, no work, was fed and given a little money!

The clay brought up from the mine made excellent bricks so a brickmaking works was started between the pit-yard and the main road leading past East Street to the Bute Arms. For years this yard made the famous Bute firebrick.

WOULD YOU BELIEVE IT:-

The population of High Spen in 1861 was, 132 males and 96 females, living in forty houses.

|

| Mrs Bullerwell in the Farmyard, 1905 |

The main road to Barlow then was from the farms at the Bute Arms past Ash Tree Farm (now gone) and over Barlow Fell. The present main road, Pawston Road was only a bridle-path.

When Matthew Atkinson was being hanged for the murder of his wife in the Old Row, the rope snapped and he fell fifteen feet. The second attempt was little better, it actually stretched and slowly strangled him. That was the last hanging at Durham.

Beda Lodge was built about 1845 for the Area Manager of the local collieries. It was and still is the finest house in the area. Its present owners Mr. and Mrs. Peter Stenner have worked hard to restore it to its previous glory.

In 1873, High Spen had its own Miners' Gala. The chief speaker was Mr. Joseph Cowan. Plenty of refreshment was provided for all who attended.

Many men died of yellow jaundice in Victoria Garesfield colliery in the 1920s. The disease was carried by rats, and as these rats ran over the miners who were lying plying their trade, the disease spread rapidly. The manager offered payment for tails, the rats disappeared and he was broke.

High Spen, in the 1930s was lucky enough to have one of the finest doctors in the area. She was Doctor Mary Livingstone who lived for her patients. She thought nothing of going down the pit; no matter how dangerous, to attend to her patients. She was beloved of all in the village.

The Bark Wood, on Barlow Fell, was so named because the bark from the oak trees was used for tanning in Winlaton. The last woman to carry a shiel of bark on her head was Bella Telford of Winlaton. She was born in 1869. The woods are named Spen Banks on the O.S. Maps.

From the 12th century onwards the farmers' labourers of Barlow and High Spen were given crowdie (corrody) for breakfast. It consisted of English Oatmeal mixed with boiling water and served with goats sheep or cows milk. I shared it with my grandfather up till 1927.

The coal owners in the area showed no mercy to the miners. Once a miner became redundant, he was evicted in a few days. Even the widows and families of miners killed in the pit were evicted. No compassion was shown, even if they had no place to go to.

When the Means Test became law in the 1930s working children left the family home to live in sheds and hen crees (houses) so that their parents would not be penalised. Many emigrated and others moved South.

A hundred and fifty years ago a plague of mice destroyed thousands of trees in Chopwell Woods.

The first Sunday School Treat for children attending St. Patrick's Church, was held on August 21st, 1886, in a field lent by Mr. Green of Bede Lodge. 240 children attended and many people contributed to the cost, among them being Messrs. Wishart, Errington, Glendinning, Cetrey, Clasper, Stewart and Clues. The vicar today would be somewhat delighted to have a Sunday School of 240 children.

In 1858 the Colliery owners erected a reading room in High Spen with a library of 130 volumes. Later the Co-op opened its own library so the miners were well looked after for reading material.

In my years at High Spen I found the people very friendly and caring. It was not always so, according to the National Press. In 1864 when Matthew Atkinson murdered his wife, Judge Mellor commented on the cowardice of the neighbours, who were fully aware of the murderous work he was engaged in but did nothing to stop it. The Times and other newspapers had leading articles upon the murder, reflecting upon the callousness of the people living at Spen.

High Spen, for over fifty years had its own Horse Show. It was usually held in the Long Field, which stretches from the present football field up to the Golf Course, alongside Chopwell Wood.

When the Colliery first opened casualties were taken away by farm cart. After a while the Colliery began its own ambulance service, using a horse-drawn vehicle. This was large and could accommodate several patients so it needed a large draught horse to pull it. One can imagine the discomfort and probable agony Of the patients as the horse plodded along the water-bound roads of those days to the R.V.I. in Newcastle. Mr. Joe Gibson, High Spen's oldest native resident (95) drove the colliery ambulance for eleven years and recounts how he would return from Newcastle and often have to feed and water his horse before returning to the Infirmary. He remembers six men being injured on one day alone. The ambulance served not only the miners but the whole village as well as Barlow and sometimes Rowlands Gill and Chopwell. About 1920 the horse-drawn ambulance was superseded by a motor vehicle, which continued till the 1930s when the State took over responsibility.

High Spen should be known as the Village of Heroes, for the men of this small colliery village, in the Great War, won two Victoria Crosses, one Military Cross, five Military Medals and two Mentions in Despatches. This is a record that no other village could equal and we should be justly proud of these fine men.

The two Victoria Crosses were won by Pte. Tommy Young and L/Cpl. Frederick William Dobson.

Mr. Tommy Young, of East Street, was a well-known figure in the village. He was a soldier in the Durham Light Infantry and received his award for rescuing several wounded soldiers under heavy shell fire. Being a happy-go-lucky fellow, he quite happily pawned his medals to buy ale for himself and his friends. The Regiment redeemed it and proudly displays it in the Museum at Durham. The award did nothing to change the personality of Tommy Young and he returned quite happily to High Spen Pit after the War, where he had many, many friends.

This was not so with L/Cpl. Billy Dobson. He worked at Garesfield Colliery as a horsekeeper and lodged for a while with Mr. Tommy Brougham at Hookergate then lived above Cumberledge's shop in Front Street. He had been a regular soldier in the Coldstream Guards and having completed his service came to work at Garesfield Colliery. When the War began in 1914 he was called up, and was drafted straight to France. In 1914 he won the V.C. for rescuing two soldiers under fire and with complete disregard for his own safety. At the Battle of Ypres he was Mentioned in Despatches and was badly wounded, and these wounds were to give him trouble all his life. After his award he was feted for the remainder Of the War but after demobilization the world was not interested in him. Employers ignored him because of his wounds and he became embittered and disillusioned. He settled in Wallsend but died in 1935, quite a young man. L./Cpl. F.W. Dobson, V.C., lies buried in Ryton Cemetery.

Before Mr. Greener bought the Palace Cinema in the 1930's, it belonged to a colourful character in Mr. John Henry Fisher. He was determined to fill his cinema and on some evenings showed two films with an interval between them. This he filled with live entertainment. Sometimes a singer or a comedian would perform, sometimes he operated the spotlight above the stage, slowly moving it around the audience, building up the tension, finally letting it come to rest on a member of the audience. This person was then presented with a voucher for a joint of meat at Mr. Cooper's shop. On one occasion he produced a woman boxer and offered a prize to anyone, man or woman who could outbox her. Joe Ward, a local pugilist, accepted the challenger and with a leer at the audience proceeded to win this easy money. Within seconds she was battering him about the stage and only the intervention of John Henry prevented him from being battered insensible.

The Hoppings were a great occasion at High Spen. In my youth they were held in the Recreation Field, beside the Field Club, but in earlier years were held at Towneley. It was here one year that a boxing booth was set up and opened. A barker harangued the crowd to find an opponent to challenge his boxer. This loud-mouthed gentleman picked on Jackie Walton a quiet chap, and after hurling insults at him, finally tossed the gloves at him, challenging him to show his manhood. Jackie sighed and put on the gloves. The barker bowed in sarcasm and introduced Jackie to the crowd, which was waiting with great enthusiasm to the contest. Unfortunately for this gentleman, Jack Walton, when roused was a holy terror and soon demolished the young boxer, he then turned and flattened the referee with a beautiful left hook. This was much appreciated by the partisan crowd.

One of the most well-known characters who came to the village when I was young was Polly Donkin from Cullercoats. Once a week for many, many years she visited High Spen to sell her fish from her large basket. Dressed in her traditional long, black fisherwoman's dress and speaking in her broad Northumbrian accent she was very popular with everyone in the village. Once a week she would travel to Rowlands Gill Station then get Annie Bessford's brake to High Spen. When she wasn't hawking her fish she was collecting for local charities for which she collected thousands of pounds.

Prior to 1913 the centre of entertainment in the village was Johnson's Gaff. This was a large wooden hut, situated behind the Miners' Arms. Mr. Bill Johnson of Front Street looked after the building hence the name, and the word "gaff" was a slang word for a cheap place of entertainment. Silent films were shown, accompanied by a piano, played to suit the film being shown.

Other forms of entertainment were shown and on one occasion a bear was introduced, and "Hexham" Jack Robson (the father of the bus owners) wrestled with it, much to the amazement of the petrified onlookers.

The hut later became the Union Headquarters of the Garesfield Lodge of Mineworkers.

Boys will be boys - and so fighting was an accepted part of life. It was forbidden to fight in the schoolyard however, so fights were arranged for after school. Once school was ended for the day, word swiftly spread that there was to be a fight and children literally swarmed to the "boxing tree". This was an oak tree which hung over the road, on Ash Tree Road. Under this tree the battle was fought. The onlookers stood around in a circle cheering on their favourites. After a while a victor emerged honour satisfied and he was escorted triumphantly away by his cronies. It is worth noting that the fight was a fair fight. Only fists were used, no kicking or rough stuff was allowed. Girls watched these fights, but seldom participated. Invariably they sympathized with the loser - so he probably didn't lose in the end!!

|

| Three Aces of Joan Fartherley's Dancing Troupe: Audrey Young, Doreen Pellet, Joan Davis |

High Spen had a very nice policeman in P.C. Riddle. He was there for many, many years and seldom if ever charged anyone with a criminal offence. he turned a blind eye to the odd person passing a betting slip (betting was against the law) or stealing a bucket of coal from the colliery. He was a most popular man and was a friend of every villager. When he retired he was succeeded by P.C. Baggs, well-named, for he very quickly started to prosecute the miners for any misdemeanours and so their lifestyle had to change somewhat.

The High Spen children were lucky to have Joan Fartherley in the village. Mrs. Fatherley had the village shop in Front Street after Mrs. Fairless and lived next door to the Headmaster of the school. Joan went to Ayton Friends School in Yorkshire, before returning to High Spen at 16 years of age. She was a fine actress and dancer and won the Royal Academy Gold Medal, a much coveted trophy. Joan used her expertise to form a dancing troupe in the village. They performed in the Palace and Co-op Halls and in other village halls to packed audiences. When the war began Joan used her talents and her troupe to raise a large sum of money for various war charities.

In 1959 the village lost an endearing old lady. Mrs Mary Jane Brown ran Brown's corner shop in Front Street for fifty eight years, right up till she died aged 83. She was a devout Methodist who regularly attended East Street Chapel and laid the foundation stone of Rowlands Gill Methodist Church. In 1939 Mrs Brown joined a Ladies Circle and knitted the record number of 315 pairs of socks for soldiers overseas in five years, an amazing feat!!

|

| Mr Bob Brown with his two sons Robert and John (1926) |

|

| Bob Brown's bus on a Field Club outing |

Her husband, Bob Brown was a fishmonger, fruiterer, carrier and bus owner over the years. In the early days he brought fish by horse and cart from North Shields Fish Quay to High Spen. This was sold with chips, from a window leading into Watson Street.

He was the first person to run a bus service from High Spen to Blaydon Station but being a gentle being he could not stand the fierce competition of Robson Brothers and soon gave up. He however adapted his carrier lorry into a bus by fixing on to it a portable frame with wooden benches as seats, and ran private trips. His sons Robert and John assisted him for a few years but Robert enjoyed driving and worked for forty years with Robson Bros. and Venture Limited.

THE END!

In 1839 the Bute Pit was well established and my story began. In 1939, a hundred years later, my story is ended.

In April 1939, with a few other boys, I Joined the 9th Bn. D.L.I., (T.A.) at Chopwell; a raw recruit being chased by Sgt. Kit Armstrong. In June I was called up with the Militia and reported to Carlisle.

The Government generously paid for me to travel extensively, and one night far away, I wrote my first poem. I sent it home to my Mother who proudly showed it to someone in the street. It found its way to the Blaydon Courier and was duly published. The following week it was attacked in the paper by a person from Chopwell, who declared me mad because of my sentiments about the village. The next week's paper however was full of letters hounding him and the locals threatened him physically in his club. I was duly impressed by this loyalty. I am including the poem in this book, but please don't be too critical - it was war-time, a time of great sentimentality!!

The pulling-down of Ramsey Street, Howard Terrace and Collingdon Road; and the fight by a resolute committee of local people to save High Spen from complete demolition, as proposed by Durham County Council, is surely another story for a later date.

THIS IS MY HOME.

(Written while serving abroad)

Not for me the town or city,

Not for me the surging throng,

But give to me my colliery village,

With the music of its song.

In days gone by, when in my youth,

I oft did curse my fate,

That I should live in such a spot,

And told myself - 'Just wait'.

But that was in the days of peace,

When life was full and raw,

Then to our village came,

The dreadful sound of war.

I joined the Army, no thought of fear,

This was my chance, I thought,

I said goodbye to my Parents dear,

But to my village nought.

I soldiered long, I travelled far,

I saw England at its best,

I travelled South, I travelled North,

I even ventured West.

I saw the cities, great and small,

I saw the countryside,

I saw the mountains, big and tall,

I saw the Ocean wide.

But when I saw these wonders all,

I also saw a mirage,

Not of beauty beyond recall,

But just a colliery village.

The colliery village is not a beauty

No artists venture near to paint,

Its gaunt grey houses sooty,

With the colliery's taunt.

It is no artist's paradise,

No camera's eye could want it,

For what beauty can arise,

That could ever warrant it.

I shut my eyes and see,

That old village, still the same,

Away up in the North country,

But how my thoughts have changed.

Once I left it with delight,

Sorrowing words I could not say,

But now I know that I was wrong,

May I go back again some day.

Not for me the town or city,

Not for me the cooped up pen,

But give to me my colliery village,

Which goes by name High Spen.

© Copyright 2000 Alex Johnson